Regulating Platform Economy in Europe: New Avenues of Research and the Emergence of a New European Social Model

Introduction

While the COVID-19 pandemic has wrought havoc in many sectors of the economy, one sector has undoubtedly boomed during the crisis: the platform economy. From food delivery to skilled freelancing, digital platforms have become household names and have helped a growing population of workers make a living during the pandemic.

Nevertheless, platform work offers a unique set of regulatory challenges for governments worldwide; these range from upholding consumer and data protection standards to maintaining a level playing field between platform firms and “traditional” employers on issues related to employment protection and tax law. Regulating the way in which technologies interact with the labor market and, more broadly, with society at large is of course not unique to the platform economy. For example, we can see how policymakers are currently attempting to grapple with thorny issues surrounding the regulation of cryptocurrencies and artificial intelligence. This short piece will examine what changes the European Union’s (EU) policy package on improving working conditions in platform work can herald for platform workers and what it might mean, in turn, for our understanding of the European social model. The EU’s policy initiative in this area is designed to introduce greater legal certainty on the legal status of platform workers and to tie platform work to employment protection legislation more closely.

After briefly discussing the contents of the proposal, I first discuss what this policy package entails for a particularly debated area in the literature on platform work – the employment status of platform workers (Sundararajan, 2016; Todolí-Signes, 2017). While the emergence of platform work has spurred vibrant academic debate in different disciplines, ranging from business management (Duggan et al. 2020) to legal studies (Aloisi and De Stefano, 2020), from industrial relations (Vandaele, 2018) to the sociology of work (Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2021), I will focus on how platform work and workers are categorized by the proposed regulatory changes. Considering the growing share of workers active in the platform economy, this topic is of unquestionable societal relevance.

Subsequently, I examine the broader regulatory backdrop against which this policy package is positioned. As the policy proposals are designed to affect EU member states’ labor markets, this discussion will necessarily have to concentrate on its European dimension. In particular, I will highlight how the proposal’s novelties in the area of employment relations fit with the idea of a European social model. This proposal on the regulation of platform firms is also notable in the light of recent actions undertaken by the EU in the field of digital governance, such as the introduction of a General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018, as well as investigations into the anti-competitive behavior in which tech giants such as Apple and Google may have (and may still be) engaged.

This legislation reveals the EU’s norm- and standard-setting ambitions regarding this new form of work. Indeed, in the communication of the proposed regulatory changes, the Commission stated that it “encourages a global governance of platform work” (p. 14), and this policy package constitutes an important step in such a direction.

As Cioffi et al. (2022) recently assessed, the EU moved quicker than other regulatory actors in the regulation of platform firms. Moreover, the approach prioritized by the EU is also notable because the impetus for change is moving from a regulatory framework, which prioritizes ex post enforcement of antitrust and competition regulations, to one that instead places greater emphasis on the socio-economic issues connected to platform work.

Rather than focusing on traditional topics related to competition policy (e.g., lower prices for consumers), Cioffi et al. (2022), argue that new attempts to regulate the platform economy are more proscriptive and more deeply embedded within societal considerations. By drawing on this distinction, this short piece examines what the proposal might entail for the regulation of platform work in Europe.

Platform work in Europe

Although measuring the economic weight of the platform economy and determining the number of people working in the sector is a notoriously difficult task (Oyer, 2020; Piasna, 2021)1, existing numbers suggest that platform firms have already reshaped Europe’s labor markets. According to the European Commission, 28.3 million European workers reported working for a platform company ‘more than sporadically’ in 2021. To put this figure into context, as of 2021, according to the EU’s statistical agency, Eurostat, 31.7 million workers were employed in the manufacturing sector – the sector that has, for much of the post-war period, been thought to constitute the economic lifeblood of advanced industrial societies.

In addition to platform work’s growing share of the EU’s labor markets, platform firms’ economic share is also increasing.

According to the European Commission, the number of individuals engaged in platform work is expected to reach 43 million by 2025 (an increase of 52% compared to the current estimate).

According to the European Council, the EU platform economy’s revenues have grown from €3 billion to €14 billion between 2016 and 2020. Food delivery services in the EU increased their revenues by 125% during the COVID-19 pandemic. The importance of the platform economy is also reflected by the sheer number of platform firms registered in the EU. A report conducted by the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) found evidence that over 500 platforms operate in the European single market.

What are the proposed changes?

In December 2021 the European Commission published a set of proposed measures designed to regulate platform work. Citing the rapid growth trajectory experienced by platform firms to justify its intervention on this issue, the Commission presented its efforts to regulate the platform economy as a timely attempt to ensure that this new frontier of work does not lead to precariousness and in-work poverty. At the time of writing, the proposal is being discussed by the European Council and the European Parliament.

The EU proposal seeks to achieve three main goals in the effective regulation of the platform economy. First, it seeks to end the regulatory fragmentation in European states on the issue of platform work. Indeed, EU member states’ national regulations on platform work have been piecemeal (Eurofound, 2021): court rulings on the employment status of platform workers have differed across member states, and national court rulings have frequently been directed at specific sectors (e.g., the Spanish ‘riders’ law’) or specific firms (e.g., Uber or Deliveroo) rather than at the platform economy as a whole. The proposals contained in the EU’s policy package are thus designed to ensure that there is one common standard applicable to all member states. Second, the proposal seeks to respond to the growing demands for clarity regarding the status of platform workers, which have been articulated in a number of bottom-up initiatives carried out by unions and grassroot activists in Europe. These initiatives seek to improve the working conditions of platform workers and aim to establish greater legal clarity on who should be/is classified as an employee (Eurofound, 2021). Third and lastly, the policy package seeks to create a supranational regulatory framework that can effectively regulate platform companies operating across borders. Given the cross-border nature of platform firms, coordinated and international action on platform firms operating in the single market is important. Some forms of platform work, such as crowd-working, integrate and accommodate platform work across borders by design, and thus necessitate the institution of international regulatory frameworks.

By aiming to establish greater clarity on whether platform workers should be classified as employed or as self-employed, the Commission aims to distinguish “genuine” self-employed workers from bogus self-employed workers. There is a real need to take action in this area, as European Commission estimates suggest that 5.5 million platform workers might be misclassified. In other words, these workers might be registered as self-employed independent contractors whereas their working relationship with platform companies may have greater similarities with an employer-employee relationship. This misclassification has consequences not only for platform workers, but also for governments, which forgo revenue streams from employers’ mandatory contributions.

An important regulatory feature present in the proposed changes is the presumption of employment (Kullmann, 2022). In prior regulations, the burden of proof for whether a platform worker is an employee or a self-employed worker lay mostly on the platform workers; however, for workers and their unions, it is challenging to bring large platform firms to court. This is why the current proposal reverses this principle, making it platform firms’ responsibility to demonstrate that they cannot be considered as employers of platform workers.

The status of platform workers: Self-employed, employees or something in between?

The ambivalent nature of platform work is a widely recognized fact. As pithily summarized by Steward and Stanford (2017, p. 421): “This gigantic marketplace might make it easier than ever for buyers and sellers to connect. But it could also facilitate a ruthless race to the bottom, as self-employed ‘freelancers’ compete in a larger, more competitive labor market to support themselves. How will workers’ traditional rights and protections fare in this brave, digital new world?” In other words, workers’ ability to gain greater work flexibility is to be counterposed to the prospect of a significant weakening in employment protections. Compared to “traditional” employers, platform firms typically offer greater flexibility and lower barriers to entry, which is especially attractive for young people with little work experience. Platform work has also become a safety net during economic downturns, especially for workers who do not live in welfare states where citizens are adequately shielded from market pressures (Oyer, 2020). Moreover, platform work offers a way for discriminated or disadvantaged groups to access the labor market (Codagnone et al. 2016). However, the emergence of the platform economy has also been deleterious on the quality of work relations: the absence of social protections, unstable income trajectories, and weakened representation rights are just some of the negative factors that are commonly associated with platform work (Prassl, 2018).

Let us now consider how this policy package affects platform firms. Although platform work is often seen as constituting yet another form of non-standard employment, the platform economy operates in a rather unique space and setting. Platform firms are at the crossroads between firm and marketplace: they frequently present themselves not as companies but rather as intermediaries or even ecosystems (Daugareilh et al. 2019). From the perspective of employment regulation, if platform firms see themselves as marketplaces rather than as companies, there is a concern that they can avoid taking on legal and financial obligations vis-à-vis their workers (Daugareilh et al. 2019; Baldwin, 2019). This allows platform firms to have a competitive advantage over traditional employers. The consequent “platformization” of firms is a well-documented phenomenon (Kenney and Zysman, 2016). Platform work might, as stated by Sundararajan (2016), be of even greater importance. as it offers an “early glimpse of what capitalist societies might evolve into over the coming decades.” (p.19) While some commentators have noted that platforms will “eat everything”, for the moment, such maximalist views do not seem to be warranted. Indeed, the re-classification of platform workers from independent contractors to employees might well eliminate one of the main advantages that platform firms have.

Re-classification would completely disrupt platform firms’ business models. Consequently, it has frequently been painted as an existential question by these businesses. To understand just how important the question of employment status is for platform firms, one might consider the case of the Proposition 22 ballot initiative in the USA. In 2019, California’s state legislature passed Assembly Bill 5, which sought to regulate the employment status of workers engaged in the platform economy. As the implementation of the bill would have led ridesharing and food-delivery companies to reclassify platform workers from “independent contractors” to employees, companies such as Uber and Lyft succeeded in passing a ballot initiative that exempted a select number of platform firms operating in California from applying the contents of the bill. While the Assembly Bill 5 and the subsequent Proposition 22 ballot initiative constitute perhaps the most notable and publicly known instances of platform firms actively trying to influence public policy outcomes, concerted efforts on the part of platform firms to convince European governments to exclude their companies from social legislation and labor codes are well-documented (Daugareilh et al. 2019; Cioffi et al. 2022). In 2022, a consortium of news outlets published the Uber Files, a database that brought to light the wide range of lobbying efforts conducted by Uber from 2013 to 2017. These leaks detailed how Uber attempted to lobby high-profile European politicians and water down existing national and municipal regulations on ride-hailing. The extensive lobbying conducted by platform firms has also been noted more recently by Elisabetta Gualmini, the Member of the European Parliament who is responsible for passing the European Commission’s proposal through the European Parliament, and who stated that she had “[…] never seen such efforts to condition and influence the activity of decision-makers.”2

The European social model and the European dimension

While the policy package published by the Commission may have important consequences for advancing the employment status of platform workers and may also serve as a first step in sketching the contours of a global governance for platform work, the regulation of platform work is particularly important for the EU for two reasons.

First, recent policy reforms in the EU have sought to ensure that the digitalization of the economy proceeds in lockstep with progress on the social dimension of EU policymaking.

Indeed, this is the stated objective and vision enshrined in the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR), which sets out a series of social goals (“headline targets”) that the EU would like to achieve by 2030 in order to establish itself as a social market economy fit for the digital age. Second, EU action in the field of platform work can provide tangible benefits to a segment of the population that has suffered disproportionately during the Eurozone and the COVID-19 crises: young low-income workers. Labor force surveys conducted across different countries have consistently shown that platform workers tend to be younger and tend to earn a lower income than workers in “standard” employment (Brancati et al. 2020; Montgomery and Baglioni, 2020).

The socially progressive objectives enshrined in the EPSR constitute a change of tack compared to the time of the Euro sovereign debt crisis, when EU policy reforms were distinguished by a distinctly pro-cyclical direction, also resulting in a series of liberalizing labor market reforms. This, as is well-known, led to a backlash against EU institutions that was particularly severe in Southern European member states, which were also the countries subject to the most taxing readjustment programs. The aim to be seen as a more socially progressive actor is manifest amongst EU policymakers and has been found to account for the increasingly social direction toward which EU policymaking has been oriented in recent years. Despite an avowed interest in positive social outcomes, the policies implemented at the height of the Euro crisis resulted in financial retrenchment. However, the idea of a European social model has proven to be a protean concept, and recent examples such as the directive on fair adequate minimum wages and on working time seem to indicate that EU policymaking has indeed shifted to a more social orientation.

European citizens have also articulated the desire to see greater EU action in social affairs. According to a 2019 Eurobarometer survey on social issues,3 88% of Europeans declared that a social Europe is important to them personally. A social Europe means the promotion of decent and fair working conditions as well as equal opportunities for citizens to access the labor market.

In this sense, enhancing social protection mechanisms for platform workers, by changing their employment status from self-employed independent contractors to employees, is part of a broader effort to ensure that European citizens are endowed with an adequate safety net.

As research has shown, self-employed workers are at a higher risk of in-work poverty than employees (Graham and Shaw, 2017). Regulating platform work, which a significant portion of workers (especially young workers) depend on financially, might well constitute a promising strategy in this regard.

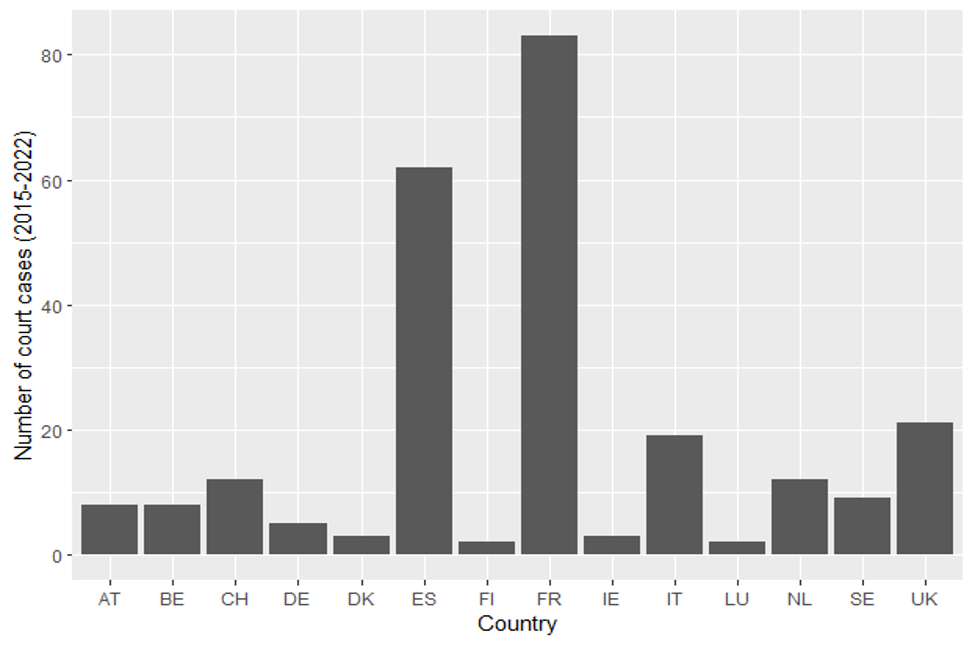

In addition, it is important to note that the regulation of platform work is not a topic that has been confined to the sidelines, but one which has become increasingly contested both electorally and judicially across many different countries (Thelen, 2018; Cini and Goldmann, 2021). The chart below illustrates the number of national and/or administrative court cases on the classification of platform workers in select European countries. While some high-profile cases involving large platform firms such as Deliveroo and Uber have attracted significant political and media attention, the data shows that since 2015 there have been over 200 judicial cases on the correct way of classifying platform workers (Hießl, 2022).

Figure 1: Number of court cases on employment status of platform workers (2015-2022). Source: Christina Hießl, Database of European case law on platform work (2022).

EU action in the regulation of platform work is thus to be considered against the backdrop of the growing political salience that this topic has acquired for European labor markets. Recent policy initiatives by the EU illustrate that this proposal also clearly has social aspirations and can be inscribed within the broader efforts of establishing a more social market economy.

Conclusion

In this piece, I have examined what the EU institutions’ re-engagement with the European social model means for socio-economic research on platform work and what it means for our understanding of notions of the European social model more broadly. While the outcome of the policy proposals is still being intensely debated, the current proposal might well be indicative of a regulatory paradigm shift in the way platform workers are categorized. At the time of writing, for example, Central and Eastern European countries reportedly seem to favor a more “liberal” approach to the classification of platform workers, whereas Mediterranean member states tend to prefer the stricter regulations put forward by the Commission. In any case, considering the proposal’s stated objective of ensuring that the EU is seen as a trend- and norm-setter, these proposals may well foreshadow how the political economy of platform work develops in other parts of the world.

Footnotes

1 – Labour force surveys often fail to adequately capture temporary and self-employed workers; categories to which gig workers are most likely to belong. For more details see Piasna (2021).

2 – Euractiv, ‘Balanced deal on platform workers rules reached, leading MEP says’, 06.12.2022.

3 – Special Eurobarometer 509 (March 2021).

References

Aloisi, A. and De Stefano, V., (2020) Regulation and the future of work: The employment relationship as an innovation facilitator. International Labour Review, 159(1), pp.47-69.

Baldwin, R. (2019) The globotics upheaval: Globalization, robotics, and the future of work. Oxford University Press.

Cini, L. and Goldmann, B. (2021) The worker capabilities approach: Insights from worker mobilizations in Italian logistics and food delivery. Work, Employment and Society, 35(5), pp.948-967.

Cioffi, J.W., Kenney, M.F. and Zysman, J. (2022) Platform power and regulatory politics: Polanyi for the twenty-first century. New Political Economy, pp.1-17.

Codagnone, C., Biagi, F. and Abadie, F. (2016) The passions and the interests: Unpacking the ‘sharing economy’. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies, JRC Science for Policy Report.

Brancati, C., Pesole, A., Fernández-Macías, E. (2020) New evidence on platform workers in Europe. Results from the second COLLEEM survey, EUR 29958 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Daugareilh, I., Degryse, C. and Pochet, P. (2019) The platform economy and social law: Key issues in comparative perspective. ETUI Research Paper-Working Paper.

De Reuver, M., Sørensen, C. and Basole, R.C. (2018) ‘The digital platform: a research agenda’. Journal of information technology, 33(2), pp.124-135.

Duggan, J., Sherman, U., Carbery, R. and McDonnell, A. (2020.) Algorithmic management and app‐work in the gig economy: A research agenda for employment relations and HRM. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), pp.114-132.

Eurofound (2021), Initiatives to improve conditions for platform workers: Aims, methods, strengths and weaknesses

Graham, M. and Shaw, J. (2017) Towards a fairer gig economy. Meatspace Press.

Hießl, C. (2022) The legal status of platform workers: regulatory approaches and prospects of a European solution. Italian Labour Law e-Journal, 15(1), pp.13-28.

Kenney, M. and Zysman, J. (2016) The rise of the platform economy. Issues in science and technology, 32(3), p.61.

Kullmann, M. (2022). ‘Platformisation’ of work: An EU perspective on Introducing a legal presumption. European Labour Law Journal, 13(1), pp.66-80.

Montgomery, T. and Baglioni, S. (2020) Defining the gig economy: platform capitalism and the reinvention of precarious work. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy.

Oyer, P. (2020) The gig economy. IZA World of Labor.

Piasna, A. (2021) Measuring the platform economy: Different approaches to estimating the size of the online platform workforce. A Modern Guide To Labour and the Platform Economy, pp.66-80.

Piasna, A. and Drahokoupil, J. (2021) Flexibility unbound: understanding the heterogeneity of preferences among food delivery platform workers. Socio-Economic Review, 19(4), pp.1397-1419.

Prassl, J. (2018) Humans as a service: The promise and perils of work in the gig economy. Oxford University Press

Stark, D. and Pais, I. (2020) Algorithmic management in the platform economy. Sociologica, 14(3), pp.47-72.

Sundararajan A (2016) The sharing economy: The end of employment and the rise of crowd-based capitalism MIT Press

Thelen, K. (2018) Regulating Uber: The politics of the platform economy in Europe and the United States. Perspectives on Politics, 16(4), pp.938-953.

Todolí-Signes, A. (2017). The ‘gig economy’: employee, self-employed or the need for a special employment regulation? Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 23(2), pp.193-205.