Q&A with Andrea Garnero – OECD Report on Labor Market Regulation

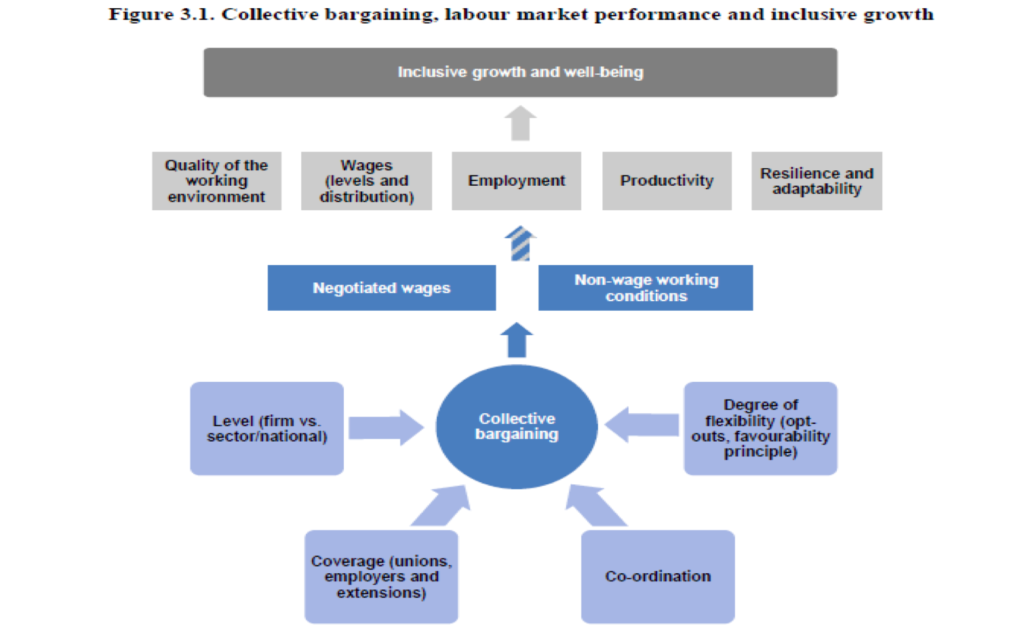

In November 2019, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released a report analyzing the structures, functions, and effects of collective bargaining and other mechanisms of workers’ voice throughout its member states. The new report, “Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work,” provides an insightful political-economic analysis of industrial relations, addressing both challenges for and trajectories of collective interest representation. Through rigorous comparative analysis, the report develops important insights into the contributions of collective bargaining and, in particular, of wage coordination mechanisms for linking national economic performance (e.g., growth, employment, and productivity) with socio-economic inequality.

On the occasion of this report, our editor Assaf Bondy interviewed one of the leading researchers behind the effort, Dr. Andrea Garnero. Dr. Garnero joined the OECD in 2014, after serving as assistant for economic affairs to the Italian Prime Minister and as an economist to the European Commission. He is a labor market economist at the Directorate for Employment, Labor, and Social Affairs of the OECD. In his work, Dr. Garnero focuses on the minimum wage and collective bargaining in OECD countries. He has been a member of the French minimum wage expert commission since 2017.

In what follows, we provide an overview of the recent report followed by the interview with Dr. Garnero. In addition to explaining the position of the OECD in political-economic policymaking, this piece aims to underline the recent change in the organization’s orientation toward collective interest representation as a central vehicle in socio-economic development.

Summary of the report

The report synthesizes information on the OECD community, reaffirming and refining previous findings about the effects of collective bargaining on socio-economic inequality and inclusion. It convincingly argues that these mechanisms are increasingly important in the face of emerging challenges, from technological change to an aging population, insofar as they provide all stakeholders with opportunities to contribute input, yielding more socially inclusive responses.

Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work, p. 109

In the report, the OECD presents an aggregate analysis of previous research of industrial relations, scrutinizing the intertwining effects of known structural variables on economic performance. But it also goes further to support workers, offering a novel perspective on possible links between different mechanisms of workers’ voice and the quality of work, broadly defined, including health and safety, training, and anti-discrimination policies. The focus on non-monetary aspects of job quality is, in itself, an important development in this analysis, stressing facets of work and their socio-political design that had largely been neglected thus far.

Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work, p. 169

Together with other recent OECD reports on industrial relations, this report attempts to go beyond traditional emphasis on flexibilization and “marketization,” underlining the importance of coordinating structures and inclusive policies. On the one hand, there remains a major (and controversial) focus on flexibility as a central component in economic growth; but on the other hand, significant emphasis is given to free and autonomous collective bargaining as a crucial vehicle for inclusive development.

While the report is important for this shift in emphasis and the use of new measures, it almost completely neglects the environmental crisis. In failing to address climate change—including its origins, risks, and possible solutions through collective bargaining—the OECD misses a crucial opportunity. Collective bargaining actors are potentially radical change agents in modern society, with the chance to propose a liberating vision for human life. The OECD can take advantage of this opportunity by linking these two issues in future reports.

Scholars of collective representation, industrial relations, and labor regulation will find the report of great interest. In addition to serving as a source of quantitative information, it also proposes new directions for qualitative work, to further expand knowledge on diverse trajectories of collective interest representation in a changing world of work. By highlighting the report, we hope to encourage more innovative research on the issues it identifies, including additional empirical tests of its claims and further theorization of its findings. Finally, we hope that the report will inspire critical work and progressive policies, to further improve the quality of work and life during these challenging times.

In recent reports, the OECD promotes new perspectives on labor market regulation and particularly on industrial relations. Can you describe these new perspectives?

Andrea Garnero: One can find the most up-to-date and complete view in the OECD “Jobs Strategy” publication, (updated for the 3rd time one year ago). The original OECD Jobs Strategy of 1994 emphasized the role of flexible labor and product markets for tackling high and persistent unemployment—the main policy concern at the time.

The new Jobs Strategy continues to stress the links between strong and sustained economic growth and the quantity of jobs, but also recognizes job quality, in terms of both wage and non-wage working conditions, and labor market inclusiveness as central policy priorities.

The main message of the new OECD Jobs Strategy is that while policies to support flexibility in product and labor markets are needed for growth, they are not sufficient to simultaneously deliver good outcomes in terms of job quantity, job quality, and inclusiveness. This also requires policies and institutions to promote job quality and inclusiveness, which are often more effective when supported by the social partners.

[The new report, “Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work,”] provides the most up-to-date and complete panorama of the state of industrial relations around the world. The report’s conclusions show that collective bargaining, when based on mutual trust between social partners and designed so as to strike a balance between inclusiveness and flexibility, is important to helping companies and workers respond to demographic and technological change and adapt to the new world of work.

It seems that the orientation of the OECD toward labor market regulation has been altered in recent years. If this is the case, what are the causes and goals of this change?

At the OECD, we are in a constant process of analysis and reflection, and the global financial crisis did not pass unnoticed.

Since the publication of the OECD’s Reassessed Jobs Strategy in 2006, and even more since the Jobs Strategy of 1994, OECD economies (as well as emerging economies) have undergone major structural changes and faced deep shocks: the worst financial and economic crisis since the Great Depression; continued weak productivity growth; unprecedentedly high levels of income inequality in many countries; and substantial upheaval linked to technological progress, globalization, and demographic change.

In light of these major changes, and the central role of labor policies in addressing them, OECD Employment and Labor Ministers in January 2016 called for a new Jobs Strategy that fully reflects new challenges and opportunities to continue to provide an effective tool to guide policy makers. The goals of this new perspective are three:

- Promoting an environment in which high-quality jobs can thrive;

- Preventing labor market exclusion and protecting individuals against labor market risks;

- Preparing for future opportunities and challenges in a rapidly changing economy and labor market.

How do these reports promote change in the political-economic policies of member or non-member states?

This is also another novelty of the latest Jobs Strategy: to support countries in building stronger and more inclusive labor markets, the new OECD Jobs Strategy goes beyond general policy recommendations by providing guidance for the implementation of reforms. A full chapter is dedicated to the political economy of reforms. And now specific country analyses are being undertaken to better forecast the effect of implementation of the Jobs Strategy at the national level.

Countries also ask for our help when discussing or preparing reforms in this field. The Government in New Zealand is working on new Fair Pay Agreement, basically reintroducing some form of sectorial bargaining, and the OECD work is cited plenty of times in their papers.

What kind of external feedback do you receive on these reports?

Before publications, all OECD reports are discussed with delegates of member countries as well as colleagues and academic or external experts.

The new Jobs Strategy and our work on collective bargaining and workers’ voice has attracted quite a lot of attention in the media as well as in the research and policy community. We are often asked to speak about it, both by governments and by unions and employers, in public events and in closed-door meetings.

From your perspective, what is the role of the OECD in producing research and recommendations?

From my experience here, the OECD plays an important role in shaping the general narrative, building a consensus on the priorities, and identifying the correct instruments for achieving these priorities.

In the 1990s, the OECD promoted the flexibilization of labor markets. More recently, we were among the first international organizations to highlight the risk linked to rising inequalities, well before it was fashionable. The OECD builds a bridge between academic research and policymaking, using what is done in academia, extending it, and, most importantly, distilling the main policy implications.

For us, academic research is our primary input. We use it to inform our analysis, to set the priorities for our own work. It’s the basis for any work we do. We start from there, we try to get the main messages, expand it where needed and, as I said, distill and develop the main policy implications, in ways that are as practical as possible.

Article and interview by Assaf Bondy